Obviously this gut feeling definition is not very helpful in our context. For any organisation only a successful culture can be a ‘good culture’, a culture which drives success. Success itself depends on the interaction of the corporation with its context – market, first of all, but also society, political set-up and some more environmental factors.

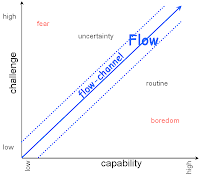

Much dispute is recently going on about corporate agility or flexibility which is declared to be more important today than ever culminating in a – like the Gartner Group called it – real time enterprise (RTE). On the other hand lots of concerns have been raised on the ever growing complexity driven by governmental regulations and other compliance necessities, by some ill-designed legacy IT or simple driven by the forces of saturated markets towards specialisation. And third we share the perception that the more the complexity of an organisation grows the less flexible it can be and vice versa.

How efficient now, how flexible should a corporation be? Well, about 2 posts back I explained that the answer to this question is not so much about free choice but seems to be determined by market forces. What we perceive as our standard organisation for large corporations is based on the scientific management dating back to the early days of last century. Those people – among who was the famous Frederick Winslow Taylor – for the conditions they found themselves being in: unsaturated markets, unlimited supply by – yet unskilled – workers, and still no automation for white collar jobs defined the industrial standard organisation.

To understand that this has not been just done by accident but there were compelling reasons for that specific outcome lets try to imagine what kind of organisation responds best to four different required characteristics: low to high flexibility and low to high complexity like in the portfolio diagram “specialisation versus flexibility”.

Let’s examine the four quadrants:

- Quadrant – Generalist in a static environment

In an environment with low change rate (static environment) and easy conditions (e.g. unsaturated market, low competition …) actors at first don’t need to be very specialized. A relatively simple organisation (low complexity) may serve the needs. The companies may thrive and grow but need not change much beyond that.

But the longer these good conditions last the more competitors are attracted. Competition increases. Finally, when there is high competition, only the strongest survives: it competes through size (economy of scale).

Such universal success models are found in nature as well: sharks exist with few changes and low specialisation since 400 million years. Dinosaurs ‘ruled’ the world for more than 160 million years – until conditions changed radically.

- Quadrant – Specialist in a static environment

Those which were less successful in the static environment either left the game or specialized into smaller niches where the big players were not able or did not want to follow.

For conquering ecological niches highly adapted efficiency specialists were required. In order to outperform the generalists they had to build a higher complexity. This excess complexity well paid off in terms of the survival of the fittest. For organisations this means, that the hierarchy needs to be overlaid by delivery relationships from special purpose groups / experts.

Niches are defined by high market entry barriers. So – for a while – the new niche dwellers were equally sheltered by these barriers as they were confined to their niches.

Wildlife offers many examples of such niche dwellers: the polar bear is perfectly adapted to the polar region - and highly endangered as this niche is threatened by global warming. The camel is another example of a highly specialized creature – in this case to deserts.

- Quadrant – Generalist in a dynamic environment

But what if environmental condition tend to change more rapidly not allowing for much specialisation and turning large and complex organisations more into a burden than into an advantage.

In this cut-throat competition scenarios flexibility turns out to be of major advantage. Flexible process innovators outperform economy of scale; the fast beat the big. Often the first mover advantage counts more than the highest efficiency or the optimal product design.

For corporations this means to leave well known and understood territory and to explore the unknown. As the right answer to new challenges is not always obvious parallel solution finding streams – aka redundancy – must be tolerated to gain at least one feasible solution within a given time frame. Also hierarchical communication turns out to be less effective. Increasing dynamics require a different organisation, hence a different culture.

In nature the wolfe is a good example. The wolfe has proven to survive under changing conditions from the arctic to the Indian jungle (remember the ‘jungle book’), from deserts to high mountains. And another new feature helps him in this game: the social system as the wolf most often does not compete as a single individual but as a collectively organized group.

- Quadrant – Specialist in a dynamic environment

And what’s about the 4th quadrant? Can it be populated as well? Are there organisations possible which are at the same time specialized and agile? So can they take advantage of “windows of opportunity” which opens just for a short while?

This is the least traditional scenario and it is hence still not well understood in terms of corporation organized appropriately to thrive in this environment.

To my understanding the swarm is the most appropriate organisational metaphor for these agile specialists: highly collectively organized nomads.

In the wild again migrating animals like migrant birds could be the solution Mother Nature has found to this challenge – after millions of trials.

Each for the four prototypic optimal organisations result in a typical organisational culture. Considering the whole chain of influences we can conclude, that the environmental conditions (market) determine the culture in the organisation.

After laying out this big picture I like to receive some comments on it. And after we have found a widely agreed model it would be the next challenge to build a metric of the corporations’ complexity and its agility. Having these metrics at hand and performing measurements of existing corporations could allow us to position them in the survival portfolio. Perhaps this would give us a diagnosis instrument for the appropriateness of a corporations organisation.